When you think of Renaissance art, you don’t just picture pretty paintings. You’re looking at a revolution in how humans saw themselves - and the world. Between 1400 and 1600, Europe didn’t just change its style - it changed its soul. Artists stopped painting saints as flat, distant figures and started showing real people with real emotion, real bodies, and real space around them. This wasn’t decoration. It was a declaration: human experience matters.

Leonardo da Vinci: The Curious Genius

Leonardo da Vinci didn’t just paint. He studied. He dissected corpses to understand muscles. He sketched flying machines decades before they were possible. His art wasn’t about perfection - it was about truth. Take the Mona Lisa. Why is she smiling? No one knows for sure. That’s the point. Leonardo captured something fleeting: a moment of thought, a whisper of feeling. Her eyes follow you because he painted light and shadow so precisely that your brain fills in the motion. He used a technique called sfumato - blending colors so softly, you can’t tell where one ends and the next begins. It made faces feel alive.

He didn’t finish many works. He got distracted. But what he did finish? They changed everything. The Last Supper isn’t just a religious scene. It’s a psychological drama. You can see the shock on each disciple’s face when Jesus says, "One of you will betray me." Each man reacts differently - some lean in, others recoil. Leonardo didn’t just paint apostles. He painted human beings in crisis.

Michelangelo: The Sculptor Who Chiseled God

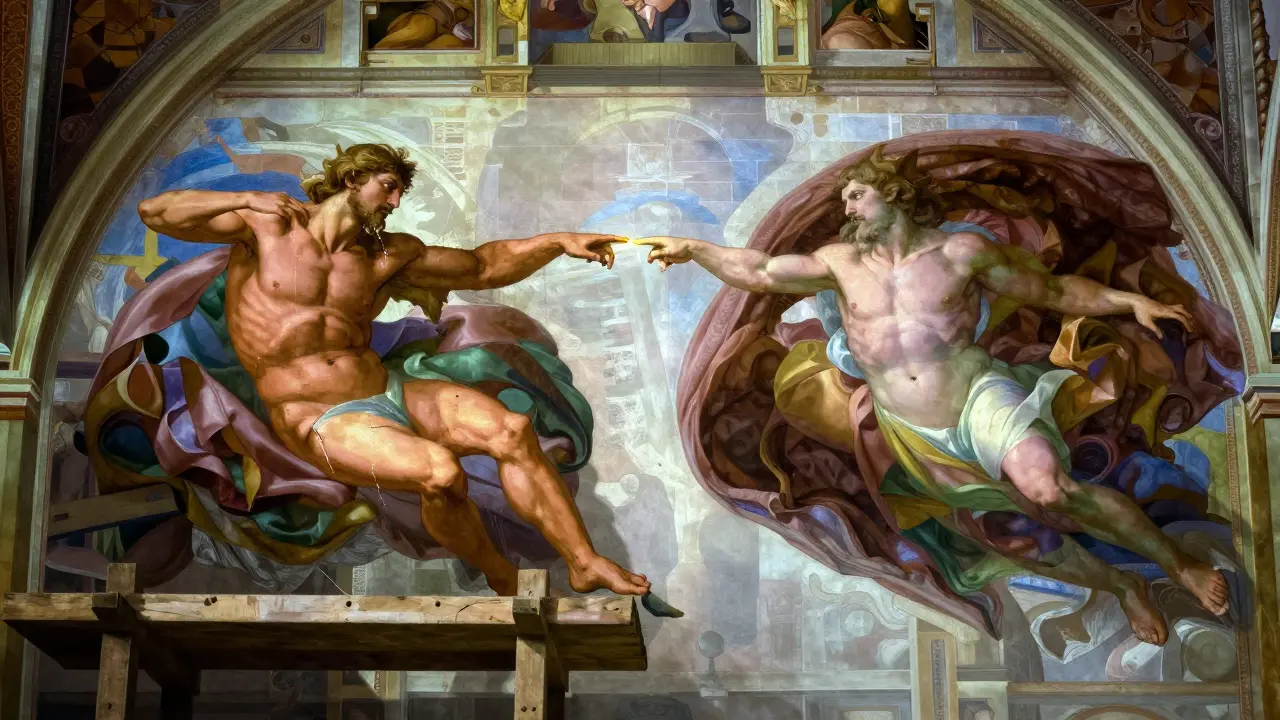

Michelangelo didn’t paint to please. He painted to prove. He was a sculptor first, and it shows. His figures aren’t floating. They’re straining. Muscles twist. Tendons pull. You can feel the effort in every line. The Sistine Chapel ceiling? It wasn’t a commission - it was a punishment. The Pope forced him to paint it, even though Michelangelo said he was a sculptor, not a painter. He spent four years lying on his back, paint dripping in his eyes, and came out with the most ambitious fresco in history.

Look at The Creation of Adam. God’s outstretched hand, almost touching Adam’s. That tiny gap? That’s the spark of life. Michelangelo didn’t show God as a bearded king. He showed Him as a powerful, moving force - a body in motion. Adam’s body is perfect, yes, but it’s also lazy. He’s not reaching. He’s waiting. That’s the tension. That’s the humanity.

His statue of David? It’s not just a hero. It’s a man about to act. David’s not holding a sling. He’s not in battle. He’s calm, focused, muscles tight, veins bulging. He’s thinking. That’s what made him different from every other statue before him. He wasn’t idealized. He was real.

Raphael: The Painter of Harmony

If Leonardo was the thinker and Michelangelo the warrior, Raphael was the diplomat. He didn’t fight for his vision. He made everyone want it. His paintings feel balanced. Calm. Beautiful without being cold. His School of Athens is a love letter to classical thought. Plato and Aristotle walk side by side - Plato pointing up to the heavens, Aristotle gesturing to the earth. Around them, philosophers from Pythagoras to Euclid are engaged in debate, not just posing.

Raphael didn’t just copy ancient Greece. He made it feel alive. The architecture behind them? It’s not random. It’s modeled after Bramante’s design for St. Peter’s Basilica - a nod to the present. He blended past and present, philosophy and beauty, in a way no one else could. His Madonnas? They’re not holy icons. They’re mothers. Gentle. Real. You can almost hear them humming.

He died at 37. He was already the most famous artist in Europe. Imagine what he could’ve done if he’d lived longer.

Botticelli: The Dreamer of Myth

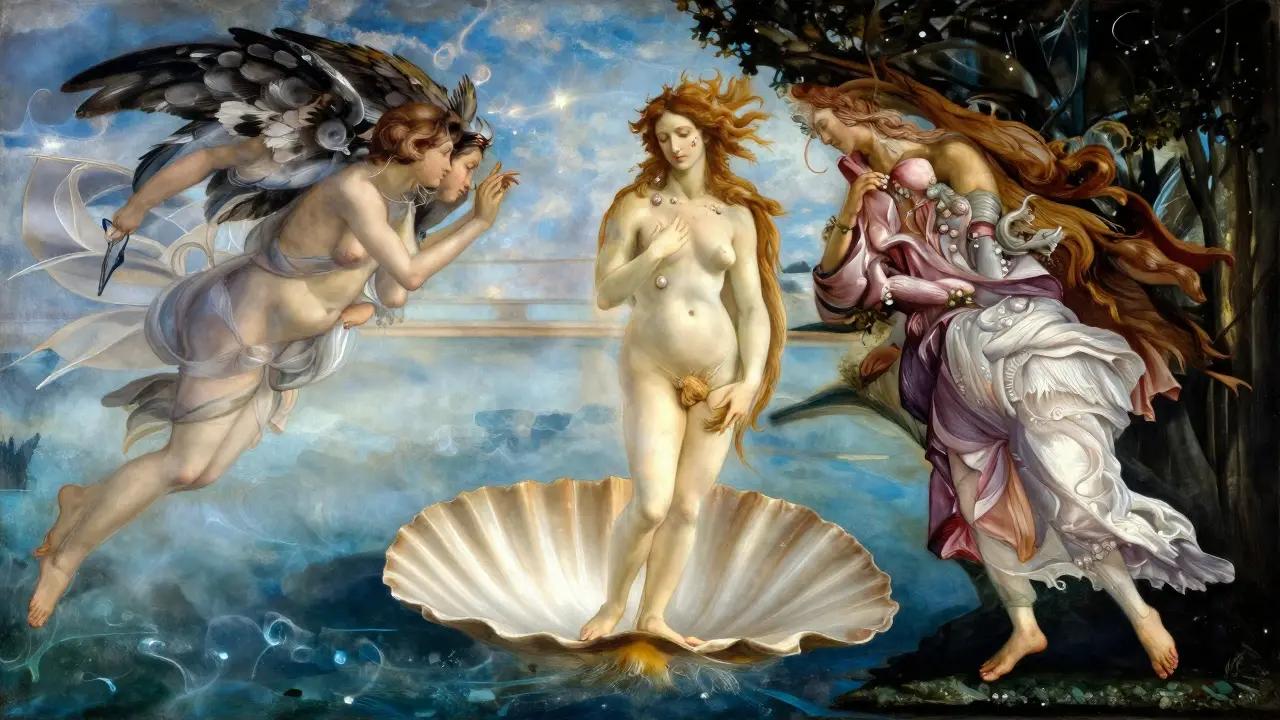

While others painted saints and scholars, Botticelli painted gods. His Birth of Venus floats on a shell, hair flowing, barefoot on water. She’s not nude to shock. She’s nude to symbolize purity, beauty, rebirth. The wind gods blow her ashore. The figure on the shore holds a cloak - not to cover her, but to welcome her. This wasn’t biblical. It was pagan. And it was revolutionary.

Back then, the Church didn’t approve of naked goddesses. But the Medici family - Florence’s richest bankers - loved it. They commissioned it. They wanted to show they were cultured, not just rich. Botticelli’s lines are soft. His colors are pale. His figures look like they’re made of smoke. It’s dreamlike. It’s not about realism. It’s about poetry.

Later in life, he turned away from myth. He painted grim religious scenes, haunted by the rise of the fire-and-brimstone preacher Savonarola. He even burned his own paintings. That’s the tension of the Renaissance: beauty and fear, freedom and control, all tangled together.

What Made Them Different?

Before the Renaissance, art was mostly symbolic. A halo meant holy. A gold background meant heaven. No shadows. No depth. No emotion.

The Renaissance changed that. Artists learned perspective - how to make a room feel deep, a road stretch into the distance. They studied anatomy. They painted from life. They used oil paint, which let them blend colors slowly, build up layers, capture light like never before.

But more than technique - they had a new idea. Humans aren’t just vessels for divine will. We’re complex. We feel. We think. We struggle. Art didn’t just show God anymore. It showed us.

Why It Still Matters

Walk into any modern museum, and you’ll see their influence. The way a portrait captures a person’s gaze? That’s Leonardo. The way a statue looks like it’s about to move? That’s Michelangelo. The way a scene feels perfectly balanced? That’s Raphael. Even today’s movies and video games borrow from their lighting, their composition, their emotional depth.

These artists didn’t just make pretty pictures. They gave us a new way to see ourselves. And that’s why, 500 years later, we still stop in front of their work. Not because it’s old. But because it still speaks.

Who were the four main Renaissance artists?

The four most influential Renaissance artists are Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Raphael Sanzio, and Sandro Botticelli. Each brought a unique approach: Leonardo with scientific observation, Michelangelo with raw physical power, Raphael with harmony and grace, and Botticelli with poetic myth. Together, they defined the era’s artistic vision.

What is the most famous Renaissance painting?

The most famous Renaissance painting is Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Its enigmatic smile, lifelike eyes, and subtle use of sfumato have captivated viewers for centuries. It’s not just the technique - it’s the mystery. Who is she? Why is she smiling? No one knows, and that’s part of its power. It’s displayed at the Louvre in Paris and draws over 10 million visitors a year.

Did Renaissance artists work alone?

No. Most worked in workshops with apprentices and assistants. Leonardo had students who helped prepare pigments and sketch backgrounds. Michelangelo’s assistants mixed plaster for the Sistine Chapel. Even Raphael ran a large studio with dozens of workers. The master designed the piece and painted the key parts - faces, hands, important details - while others handled less critical areas. Collaboration was standard, not the exception.

How did religion influence Renaissance art?

Religion was still the main source of commissions - churches and wealthy patrons wanted biblical scenes. But Renaissance artists began to treat religious figures as real people. The Virgin Mary became a loving mother, not a distant symbol. Christ’s suffering looked human, not staged. Even in sacred scenes, artists added natural landscapes, realistic architecture, and emotional expressions. Religion provided the subject, but humanity provided the soul.

What materials did Renaissance artists use?

They moved from tempera (egg-based paint) to oil paint, which dried slower and allowed for richer colors and smoother blending. They painted on wooden panels, then later on canvas. For frescoes, like Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, they painted on wet plaster. Gold leaf was still used for halos, but less frequently. Pigments came from minerals - lapis lazuli for blue, vermilion for red - and were ground by hand, making them expensive and rare.

What to See Next

If you want to go deeper, start with the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. That’s where Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Raphael’s Madonna of the Goldfinch hang side by side. Then head to the Vatican Museums for the Sistine Chapel and Raphael’s rooms. In Milan, see The Last Supper - though it’s fading, you can still feel its power. And in Paris, stand in front of the Mona Lisa - yes, it’s smaller than you think. But it’s still the most watched face in the world.

The Renaissance didn’t end with the last brushstroke. It ended when we stopped seeing art as decoration - and started seeing it as a mirror.