Baroque architecture doesn’t just stand in a city-it commands attention. You see it in the sweeping curves of a cathedral facade, the wild swirls of gilded stucco, the way light pools dramatically across a marble floor. This isn’t subtle design. It’s theater in stone and plaster, built to overwhelm, to inspire awe, and to make you feel small in the presence of power-whether that power came from the Church, a king, or a wealthy merchant. If you’ve ever walked into a Baroque church and felt your breath catch, you’ve already felt its language. Now, let’s learn how to read it.

What Baroque Architecture Actually Looks Like

Baroque architecture exploded across Europe between 1600 and 1750. It started in Rome, fueled by the Catholic Church’s desire to reassert its dominance after the Protestant Reformation. The goal? Make faith feel alive, emotional, and undeniable. That meant ditching the calm symmetry of Renaissance buildings for movement, drama, and illusion.

Look closely at a Baroque facade. It’s rarely flat. Walls bulge outward in convex curves. Columns twist like ropes. Pediments break into fragments. Windows aren’t just openings-they’re framed by sculpted figures that seem to lean out, as if trying to join you. The whole structure feels like it’s in motion, frozen mid-dance.

Inside, the illusion gets even wilder. Ceilings are painted to look like open skies, with angels tumbling down from clouds that don’t exist. Architects used forced perspective to make halls feel longer than they are. Light isn’t just let in-it’s choreographed. Sunbeams hit altars at specific times of day, turning gold leaf into fire. This isn’t decoration. It’s stage design for worship.

The Building Blocks of Baroque Language

Every element in Baroque architecture has a role. It’s not random. Here’s what to look for:

- Broken pediments: Triangular tops of doorways or windows are split open, often with a statue or scroll spilling through. This breaks the rigidity of classical design and creates tension.

- Twisted columns (Solomonic columns): These spiral columns, inspired by ancient legends of Solomon’s Temple, twist like vines. They’re everywhere in Baroque altars and pulpits.

- Ornate stucco work: Walls aren’t painted-they’re sculpted. Flowers, cherubs, and ribbons swirl across ceilings and cornices, often gilded or painted in soft pastels.

- Grand staircases: Not just functional, these are showpieces. Think of the staircase at the Würzburg Residenz-wide, sweeping, lined with frescoes, designed so visitors arrive at the throne room like royalty.

- Chiaroscuro effects: Light and shadow aren’t accidental. Architects planned where sunlight would fall, creating dramatic contrasts that highlight altars, statues, or portraits.

These aren’t just details. They’re grammar. A twisted column isn’t just pretty-it signals divine energy. A broken pediment isn’t a mistake-it’s rebellion against order, a visual shout of emotion.

Baroque in Different Countries

Baroque didn’t look the same everywhere. Local tastes and materials changed the language.

In Italy, especially Rome, it was pure spectacle. Bernini’s St. Peter’s Square, with its colonnades embracing visitors like arms, was designed to draw pilgrims into the Church’s fold. The interior of Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza looks like a spiral seashell made stone-complex, organic, alive.

France tamed Baroque. Louis XIV’s Palace of Versailles still has gilding and grandeur, but it’s more controlled. Symmetry returns. The gardens are geometric. The emotion is restrained, channeled into power rather than ecstasy. French Baroque is about royal authority, not divine mystery.

Spain and Latin America took Baroque to extremes. In Mexico City’s Cathedral or the Church of San Francisco in Quito, every surface is covered. Gold leaf, carved wood, and painted tiles create a dizzying, almost overwhelming richness. This was the Church’s way of converting indigenous populations-beauty as a tool of faith.

In Germany and Austria, Baroque became almost fantastical. The Würzburg Residenz and the Basilica of the Fourteen Holy Helpers feel like dreams carved in marble. Ceilings burst with angels, walls dissolve into painted skies, and light floods in from hidden windows. It’s Baroque as spiritual cinema.

Why It Matters Today

Baroque architecture isn’t just a relic. It’s a lesson in how design shapes emotion. Modern buildings often aim for calm, clean lines. Baroque does the opposite-it pulls you in, makes you feel something. That’s why it still works in places like the Vienna State Opera or the Palácio Nacional de Mafra in Portugal. People don’t just visit them. They’re moved by them.

Even today’s luxury hotels, high-end restaurants, and boutique stores borrow from Baroque. Velvet drapes, gilded mirrors, curved marble counters-they’re all echoes of a time when design was meant to dazzle. You don’t need a dome or a fresco to feel the influence. Sometimes, it’s just a single twisted column in a bathroom faucet, or a ceiling that seems to rise too high.

How to Spot a Baroque Building

Next time you’re in a city with old churches or palaces, try this:

- Look at the facade. Is it flat and balanced? Then it’s probably Renaissance. Is it swirling, bulging, broken? That’s Baroque.

- Check the columns. Are they straight? Classical. Are they twisting? Baroque.

- Look up. Does the ceiling look like it’s opening to heaven? That’s a Baroque fresco.

- Notice the light. Does it hit one spot like a spotlight? That’s intentional.

- Walk around the building. Does it feel like it’s moving toward you? Baroque architecture often pulls you in, never pushes you away.

You don’t need an architecture degree to see it. You just need to stop and look.

Baroque vs. Rococo: The Next Step

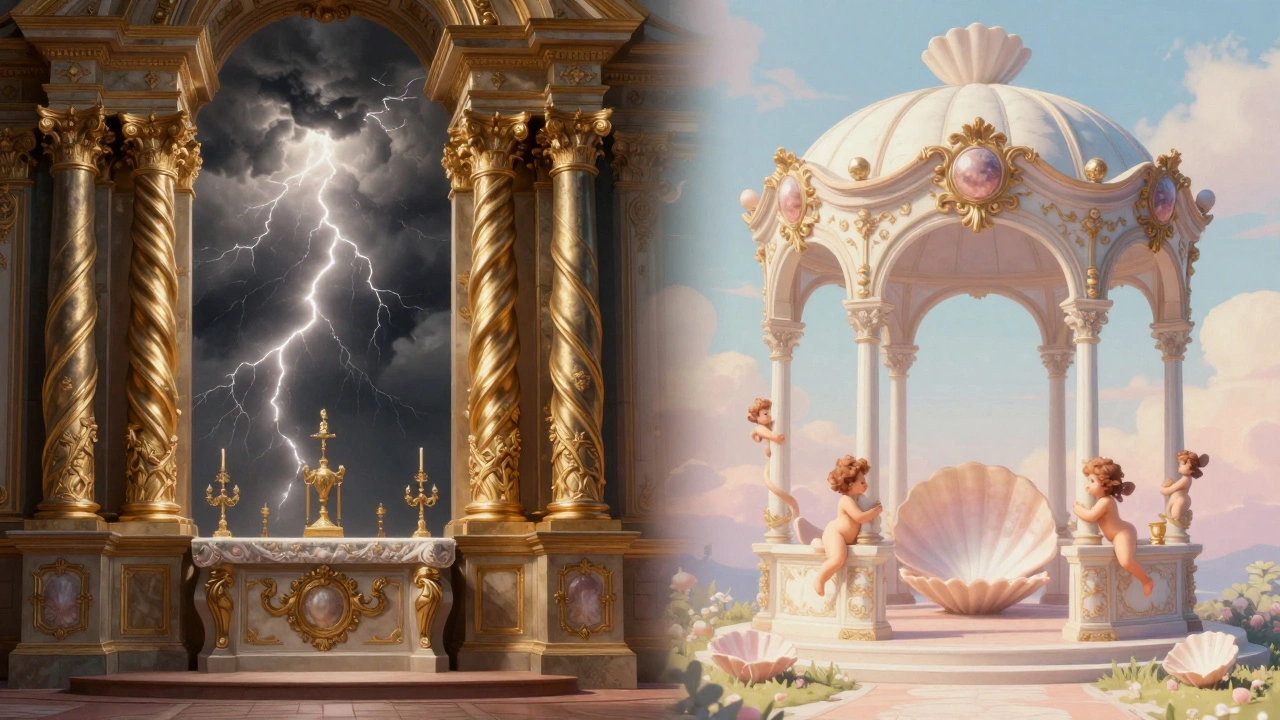

Baroque didn’t end-it evolved. By the 1730s, a lighter, more playful version emerged: Rococo. If Baroque is a thunderstorm, Rococo is a butterfly.

Rococo keeps the curves and ornament but ditches the drama. Think pastel colors, delicate shells, and whimsical cherubs. It’s less about awe and more about charm. The Amalienburg Pavilion in Munich is pure Rococo-elegant, airy, almost too sweet. Baroque says, "God is mighty." Rococo whispers, "Isn’t life lovely?"

Knowing the difference helps you read the timeline. Baroque came first-bold, loud, religious. Rococo followed-refined, personal, secular. Both are part of the same family, but they speak different dialects.

Where to See the Best Examples

If you want to experience Baroque architecture at its peak, these are non-negotiable stops:

- St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome: Bernini’s colonnade and baldachin are the textbook definition of Baroque grandeur.

- Würzburg Residenz, Germany: The staircase and ceiling fresco by Tiepolo are among the most breathtaking in Europe.

- Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Rome: Borromini’s twisted columns and undulating walls are pure architectural genius.

- Palácio Nacional de Mafra, Portugal: A massive palace-monastery complex with over 1,200 rooms, built in a single wave of Baroque ambition.

- Church of the Gesù, Rome: The first Baroque church, setting the template for every one that followed.

These aren’t museums. They’re living spaces. People still worship in them, walk through them, sit in their pews. The language hasn’t faded-it’s still speaking.

Why We Still Feel It

Baroque architecture works because it speaks to something deeper than aesthetics. It taps into emotion. In a world of flat screens and minimalist interiors, we still crave spaces that make us feel something. Baroque doesn’t ask you to be calm. It asks you to be moved.

That’s why, even today, when someone wants to create a sense of awe-whether in a luxury hotel lobby, a concert hall, or a grand entrance-they turn to Baroque. Not because it’s old. But because it still works.

What makes Baroque architecture different from Renaissance?

Renaissance architecture is balanced, calm, and based on classical rules-think symmetry, proportion, and restraint. Baroque throws all that out. It’s dynamic, emotional, and dramatic. Where Renaissance buildings feel like a perfect equation, Baroque feels like a symphony in motion. Columns twist, walls bulge, ceilings open to heaven. It’s not about order-it’s about impact.

Is Baroque architecture only religious?

No. While the Catholic Church drove its early spread, Baroque was also used by kings and wealthy families to show power. Palaces like Versailles and the Würzburg Residenz are secular Baroque. The same techniques-grand staircases, gilded ceilings, dramatic lighting-were used to impress visitors and reinforce authority, whether divine or royal.

Can Baroque architecture be modernized?

Yes, but not by copying it. Modern architects borrow its emotional power, not its details. A contemporary building might use dramatic lighting, curved forms, or layered materials to create awe-without gilding or cherubs. The spirit of Baroque-making people feel something-is what’s timeless, not the ornament.

Why do Baroque buildings have so much gold?

Gold wasn’t just for show-it was symbolic. In religious buildings, it represented divine light and eternity. In palaces, it signaled unlimited wealth and power. The reflective surface also helped amplify natural light before electric bulbs. More than decoration, gold was a tool to manipulate perception and emotion.

Are there Baroque buildings outside Europe?

Absolutely. Spanish and Portuguese colonists brought Baroque to Latin America, the Philippines, and parts of India. Churches in Mexico City, Quito, and Goa are packed with local materials and indigenous motifs, fused with European Baroque forms. These are some of the most intense and colorful examples of the style.