Our world is a tapestry of intricate social patterns and structures, shaped largely by the concept of functionalism. This influential theory suggests that every component of society serves a purpose, contributing to the overall stability and functioning of social systems. From the family unit to expansive governmental bodies, each plays an essential role in maintaining societal balance.

Functionalism helps us explore the societal norms that guide our everyday interactions. It provides us with a lens through which we can examine why societies maintain certain values, how social change occurs, and the interdependence of various institutions. By delving into the roots and implications of functionalism, we gain insight into the seamless choreography that keeps the social machine running smoothly.

- Understanding Functionalism

- Historical Context and Development

- Role of Social Institutions

- Impact on Societal Norms

- Critiques and Modern Adaptations

Understanding Functionalism

Functionalism is a theory in sociology that views society as a complex system composed of many interconnected parts, each with its own specific function. This approach helps us understand the myriad ways in which different social institutions contribute to the stability and endurance of society. By focusing on the roles that each component plays, functionalism provides a framework for analyzing how societies maintain internal equilibrium. Functionalist theorists, like Émile Durkheim, have suggested that social institutions fulfill necessary roles to keep communities stable and cohesive.

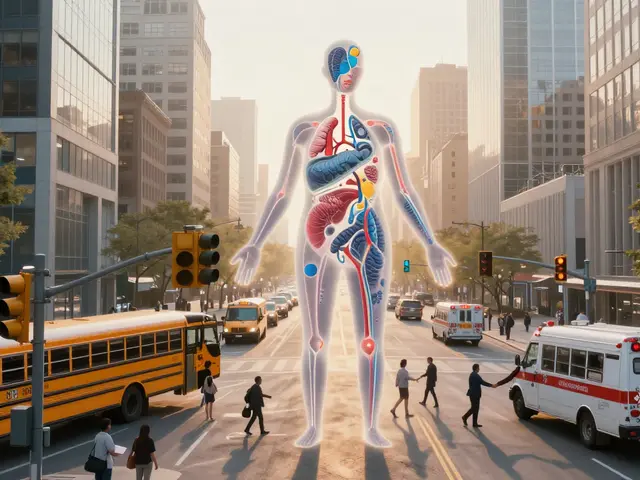

In functionalism, society is seen through the metaphor of a living organism. Just as an organism relies on the cooperation of distinct organs to survive, so too does society depend on its social systems and structures. Institutions such as the family, religion, and education serve as the ‘organs’ of this societal body, each fulfilling critical needs. For instance, the family nurtures future citizens, religion provides moral guidance, and education transmits essential knowledge. These elements work in concert to produce social order and control, highlight power imbalances, and respond to the common needs of individuals within the social fabric.

Durkheim once noted, "Society is not a mere sum of individuals. Rather, the system formed by their association represents a specific reality which has its own characteristics."

Functionalism emphasizes how societal norms emerge from these essential interactions, shaping behaviors and guiding the values that underpin community life. This perspective also examines how disruptions in social patterns can lead to societal change—inevitably striving to return to equilibrium, much like disease prompts adjustments in a biological system. An apparent change, like adapting to technological advancements, forces social systems to adjust their roles and expectations accordingly, ensuring their ongoing functional necessity.

One of the key advantages of functionalism is its ability to create a comprehensive model of society that intricately ties together diverse social phenomena. While critiques argue that it often overlooks social conflicts, functionalism’s focus on stability and cohesion offers valuable insights into why societies develop specific norms and behaviors. As such, it remains an invaluable theoretical approach for understanding how society functions in sync, despite the ever-changing landscape of human needs and developments.

Historical Context and Development

The roots of functionalism can be traced back to the early works of Auguste Comte, who is often regarded as the father of sociology. Comte's vision of society was as an organism, each part essential to the whole's health. His compelling analogy laid the groundwork for understanding how societal elements contribute to stability. Later, the French sociologist Émile Durkheim expanded on these ideas, emphasizing that social structures, much like biological ones, function to maintain solidarity and prevent societal disintegration. Durkheim's seminal work, 'The Division of Labour in Society,' highlighted how societal order is achieved when parts work in harmony.

Building on these ideas, Talcott Parsons was pivotal in the development of modern functionalist theory during the mid-20th century. He proposed a framework where society operates by fulfilling four functional necessities: adaptation, goal attainment, integration, and latency, known as AGIL. Through this lens, every institution, from education to religion, has a role in fulfilling these needs. His work offered a comprehensive understanding of the social system's persistency and cohesion, shaping modern sociology immensely.

Talcott Parsons once remarked, "All social structures must perform these requisites, else face inevitable decline." His words encapsulate the essence of functionalism in social longevity.

Amidst these foundational contributions, the machine of sociology was continuously refined and critiqued. Robert K. Merton introduced the concept of 'dysfunctions'—unintended consequences of social processes that may disrupt society. This nuanced perspective highlights that not every societal function ensures stability; sometimes, the dysfunctions call for reform or change. The evolution of functionalism also acknowledges the complexities of modern, pluralistic societies, where multiple narratives and functions coexist and sometimes clash.

Interestingly, the rise of structural functionalism paralleled the era of industrialization and modernization. This period saw societies transforming rapidly, driven by technological advancements and shifting economic practices. The notion that social systems could be understood as a set of functions mirrored the mechanistic view of industrial machinery, bringing forth a unique perspective on societal progress. Statistical studies of the time supported these theories, illustrating how institutions like family and education adapted in response to new social demands. As more individuals migrated to urban centers, traditional norms evolved, showcasing functionalism in action.

Historically, the extent to which social structures contributed to norms has been a matter of debate. Despite criticisms, particularly from proponents of conflict theories like Marxism, functionalism remains a crucial analytical tool. It allows sociology to map out how communities not only survive but thrive during change. Progressive shifts in the modern sociological landscape recognize that while functionalism may not account for every aspect, its foundational principles underpin many contemporary theories. This progression from past to present illustrates that while societies evolve, the core idea of leveraging social functions to drive stability remains potent.

Role of Social Institutions

The bedrock of any thriving society is the presence of strong, organized social institutions. These institutions are the invisible hands orchestrating much of our social landscape, ensuring coherence and guiding the collective human experience. From educational systems that impart crucial knowledge to healthcare frameworks dedicated to public well-being, these institutions lay the groundwork for a functioning society. They aren't just formal structures—they are the vessels through which human behavior is shaped, norms are established, and societal values are passed down through generations.

Consider the role of the educational institution. It is here that individuals first learn to navigate social hierarchies, foster friendships, and understand cultural understandings. Education goes beyond textbooks; it builds the collective conscience and equips people with the ability to critically engage with their surroundings. According to Emile Durkheim, a pioneering sociologist, education serves as a societal agent of cohesion, promoting shared values and cultural heritage.

"Education is the transmission of civilization," noted Will Durant, an American writer and philosopher, further emphasizing the idea that it is a vital pillar in maintaining societal continuity.

Functionalism speaks to how institutions such as the family unit operate as the primary socialization site for individuals. The family molds character and introduces basic societal norms, becoming the cornerstone of social development. It is here that children learn empathy, respect, and discipline—virtues that later influence every facet of their lives. The persistence of these norms is mirrored in religious institutions, which often overlap with family ideals by further embedding moral codes and ethics. Churches, mosques, and temples, among others, cultivate a shared belief system, cementing a community’s foundation through tradition and spiritual connectivity.

Political institutions, too, wield significant roles in shaping social norms, often acting as arbiters of justice and power distribution. They craft policies that affect every layer of society, from economic regulations that influence wealth distribution to laws that demarcate right from wrong. By molding societal expectations and rules, these structures maintain equilibrium and ensure orderly progression within civilizations. It's noteworthy how different social security systems impact poverty levels across nations, highlighting the pivotal role politics play.

The sociological perspective on functionalism also recognizes economic institutions as pivotal players in the societal framework. These entities not only influence production and consumption patterns but also impact social identity and personal ambitions. The labor market defines what is valued in society, affecting job creation, skill development, and gender roles within the workplace. Economic institutions thus serve as both the suppliers of life's necessities and the arenas where new social norms emerge, reflecting and responding to the ever-evolving societal climate.

Lastly, media and technological institutions have emerged as grand architects of modern societal norms. By shaping public perceptions and facilitating instantaneous cross-cultural exchanges, they wield unparalleled power over public opinion. This dual ability to inform and connect makes them key players in the daily lives of individuals, as they create avenues for cultural exchange and global understanding. Given the rapid pace of technological advances, understanding how these institutions influence societal norms is more important than ever, particularly in adolescence, when media consumption is most frequent. Analyzing these roles reveals a fascinating interplay between ancient traditions and present-day innovations, with functionalism offering a unique, holistic view of how society evolves.

Impact on Societal Norms

Functionalism has a profound impact on how societal norms are established and adhered to over time. At its core, the theory views society as a cohesive system where various parts work together to maintain equilibrium. These parts could be institutions such as schools, churches, families, and governments, all functioning to instill and perpetuate social norms. For instance, educational systems teach societal values and expectations, preparing individuals to participate meaningfully in society. They serve a critical role in socializing young members, ensuring the transfer of cultural norms and ethics. This organized transmission of knowledge and values assists in maintaining a society’s cohesion and continuity.

One remarkable aspect of functionalism is its ability to explain social order through a structured framework. Consider the family unit; it plays a vital role in nurturing and preparing future generations. This essential institution instills basic norms like respect, cooperation, and responsibility. Such norms are pivotal as they become the building blocks of a functional society, leading to a collective sense of identity and integrity. Without these underlying systems, societal disarray might ensue, leading to breakdowns in communication and understanding. Functionalism suggests that every established norm answers a significant societal demand, from the minor customs to comprehensive legal frameworks.

Emile Durkheim, a prominent figure in functionalism, once noted, "Society is not a mere sum of individuals; rather, the system formed by their association represents a specific reality which has its own characteristics."This insightful perspective allows us to appreciate how vast the influences of collective entities are beyond individual actions. Modern communities continue to be shaped by these foundational principles, adapting established norms to cater to contemporary demands. The continual evolution of social norms highlights the dynamic nature of human societies.

Despite some criticisms, functionalism provides a robust understanding of how societal norms are not only created but also continuously reinforced. Imagine a society without systems to uphold justice or health; chaos would reign. Functionalism stresses that laws and healthcare systems are indispensable to maintaining the stability and functionality of societies. Services like policing and public health are grounded in legal and ethical norms that echo the collective values of society. The adaptability of these rules and institutions to changing social conditions showcases the flexibility required to meet societal needs today.

To better illustrate the role of functionalism, let's consider an example from everyday life. In most communities, traffic laws are essential norms designed to maintain public safety. By prescribing specific behaviors on the road, such regulations function to prevent accidents and promote harmony among road users. These norms are enforceable by authority figures and are generally accepted by the members of society, showcasing an intricate interplay of law, order, and community well-being. Thus, norms such as this underscore the significant function they serve and the critical balance upheld by functionalist principles.

In summary, functionalism illuminates the importance of established social norms in sustaining societal balance. By analyzing foundational institutions and their roles, we gain insight into the principles that guide social conduct and values. The influences of societal norms extend beyond mere customs or traditions, shaping the essence of community life. Functionalism, therefore, remains a rich area of study as we navigate and understand the complexities of modern societies.

Critiques and Modern Adaptations

Critiques of functionalism have been a pivotal part of its evolution, with scholars and thinkers challenging its fundamental notions for decades. A primary criticism is aimed at its presumption of societal stability and cohesion while often overlooking social conflict and inequality. Critics argue that societal norms are not always functional for all members of society, especially considering historical contexts of oppression and marginalization. This perspective highlights how functionalism might gloss over the dynamics of power and stratification, thus failing to address injustices embedded within social structures.

One of the more prominent voices in these critiques is that of C. Wright Mills, who questioned the empirical validity of functionalism and suggested that it is overly deterministic. He criticized it for neglecting individual agency, which plays a significant role in shaping social change.

"Functionalism, with its grand generalizations, often misses the subtleties of human action and the intricate dance of individual choice and social structure," Mills once noted. This insight, among others, has sparked movements towards theories that incorporate more fluid and dynamic interpretations of society.

Adaptations of functionalism have evolved in response to these critiques, leading to neo-functionalism—a contemporary iteration attempting to integrate elements of conflict theory. Neo-functionalism acknowledges the potential for change and adaptation within the social systems, recognizing that institutions and norms are not static but evolve with shifts in cultural and historical landscapes. This perspective is pivotal in addressing the criticisms of rigidity, giving room for human agency and cultural variations.

In light of these modern challenges, functionalism has seen a rejuvenation in its methodologies. Current sociologists are reintegrating micro-level analysis into macroscopic frameworks, creating a more balanced viewpoint that considers the intricacies of both individual interactions and overarching social trends. They explore how technological advancement, globalization, and cultural exchange are reshaping traditional social structures, prompting reinterpretations of classic functionalist ideas for a modern world.

Data supporting these adaptations are evident in studies comparing rates of change in various social institutions across geographical and cultural contexts. For example, when examining educational structures, there's a noticeable shift in emphasis from standardized testing to holistic education approaches.

| Country | Traditional Structure | Modern Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| USA | Standardized Testing | Project-Based Learning |

| Japan | Rote Memorization | Collaborative Problem Solving |